A little story today. It goes like this. I drop by one of our teams, and within completely different discussion I get asked this very “simple” question:

“Can we overlay an actual development team cost on top of product revenues so that we know if we are in the red or in the green?”

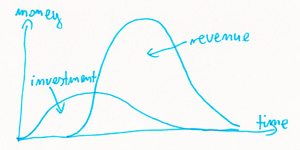

If you haven’t noticed yet, there’s a flaw in this question. The problem is, it simply doesn’t make sense from economic point of view. For any project in any industry one thing is true: investment into project comes before realizing profit from that project. It’s pure logic, you just can’t defeat causality. Depending on the industry the distribution of investment and revenue over time axis will differ, but it might look like this:

This offset between investment and revenue is the core of the problem: current development costs are always out of sync with current revenue. Depending on the industry and project the gap will obviously vary but it’s always there. This is relatively simple and intiuitive concept when we talk about project-based work but it becomes somewhat more complex when we talk about online games, which are services. Some successful online games (like World of Warcraft) have been with us for a long time, but this is only because their developers keep working on them. In other words, the investment is continuous, and so is revenue (both curves do not have to be smooth!). These games wouldn’t have survived if they remained static in their entire life cycle, they evolved and changed together with their player base. In the world of game services, there’s huge overlap between the two curves from graph above but the truth remains: current investments create future profits. Nothing new here, move along, and of post? Not really, this is where the fun actually begins.

Let’s talk about something I decided to call service decay model. What happens to the service once we completely stop development and leave only essential stuff: server operations, customer support, traffic acquisition? How long before it no longer makes sense to keep it running? If the product becomes static, it will continue to make money, only less and less every month. The decline does not happen overnight, and the tail is very long, but (with rare exceptions) we can safely assume that there’s some upper cap on total profits that we can extract from service in the period between now and before killing it completely at some unknown point in future. This upper cap is life time value (LTV) of a service. Let’s call it LTVS, I love abbreviations (on a more serious side, economists/financial folks probably have some more established name for this). We have no way to know LTVS, we can only try to build model that predicts it. Building predictive models is so hardcore math that Steve Jobs would just say it’s magical (you should build that model anyway, just because everyone sucks at predictions). What is interesting is that LTVS lets us define the value of current development: it is the change it causes to LTVS. In other words: The feature is profitable if the increase in future revenue is bigger than the cost of implementing the feature. To put it in pseudo equation form: Cost(feature) < delta LTVS. Why is that stuff important?

- When you are early in the service life, it is “sink or swim”, it has to grow or you should just cut your losses and move on.

- When you are late in the service life, you should stop development way, way before you are in the red (in terms of service revenue vs development costs). When? When you no longer add value.

- If your service gets huge, economy of scale comes into play - 0.1% improvement might still be worth it if you have 10M users.

- Pulling the plug on service (killing it from end user perspective) may come long time after dev team moved on to other stuff.

By the way, this explains how larger companies came to the idea of separate product development (whose task is to deliver a product/service or make specific improvement/change in it) from operations (which is responsible for running the service day to day) and from marketing (which does user acquisition and community management). In theory it makes sense, but it also creates organizational silos and internal handoffs, along with numerous negative effects. You have been warned. An interesting (even if slightly bitter) thought to end this post is something I saw on Twitter few days ago: “There are two kinds of product features, those that improve product value, and those that justify someones job”.